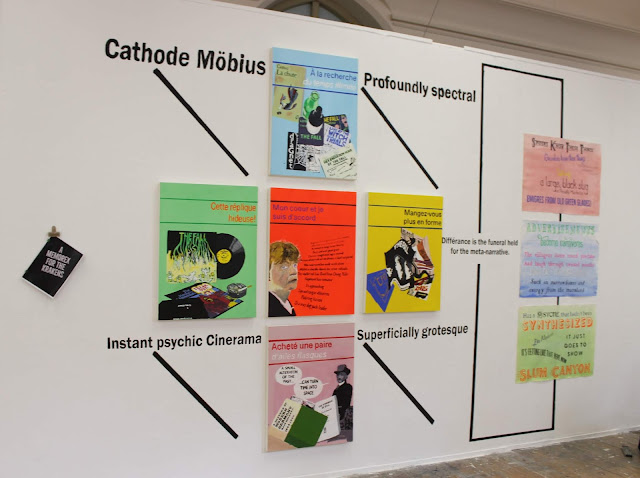

Two Steps Back: a Critique of Today, a Dismissal of the Past and a Eulogy for the Future, as Presided over by Mark E. Smith and The Fall

“I had come to loathe my

husband, Mr Harlax. I mean, physically,

be revolted by him. I could look at him

and think only of the functions.”

-

Artemis ‘81

Différance

is the funeral held for the meta-narrative.

Memorex. Manufacturer of computer peripherals and

recordable media. Established in 1961,

Memorex were synonymous during the 1980s with home recording.

Kraken. Legendary squid-like sea creature said to

wrap its tentacles, once disturbed, around vessels and drag them to the bottom

of the ocean.

The

time of year I remember most distinctly from my childhood were those strange

weeks when the nights drew in.

Halloween, Bonfire Night…the cheap masks at the shop at the end of the

twitchel (because that’s what they were called in North Nottinghamshire), the

divine aroma of potatoes being charred on the backyard fire which, in our age

of ultra-safety, would never be bureaucratically tolerated. Those cold, dark evenings carried their own

gothic magic as a child. One could quite

easily imagine Spring-Heeled Jack

bounding from the council estate roofs and the bizarrely-gnarled trees in the

woods actually being science fiction organisms.

Renowned as one of the most haunted villages in England, the remains of

an old Roman garrison sat atop the clay hill which hamletted the village on all

sides. There was always a spectral

threat on the lips of our parents, and all of this has indelibly left a

quasi-Victorian gothic impression on my recollections of the early eighties.

To

begin, then, with the problematic word. When

we say “haunting,” we are tacitly referring to the ineffable: concepts which,

when attempted to give form to or study, vaporise. Something altogether apart from philosophical

immanence, this is the run-out groove which carries the fading analogue

vibrations of our specific pasts, and if words such as “haunting,” “ghosts,”

“spectres,” (ad nauseum) are to

characterise memory this is only because these terms serve best to outline a

difference which cannot be described in binaries. We may, if we are so inclined, steer off

track and cite Bergson at this point though it serves just as well to propose

that memories are recalled in units, rather than successive elements of

time. Were we to recall perfectly our

entire lives in reverse beginning with the absolute present then we would

doubtless pick up on subtle ideological or cosmetic shifts in our

environs. We would, however in all

probability miss the greater shifts and distinctions, but given that this kind

of recollection is impossible, we instead focus on the event. These events, as unitary measures, are

themselves “haunted,” as it were, by dead elements (be they cars which are no

longer on the road, a foodstuff no longer manufactured or a television

programme that nobody else remembers being aired). We may then say that we are haunted by the

event, or even the unit.

This

is hinted at by Derrida, yet made explicit by the 21st Century

permutation of Hauntology. Our factually

oblique and rose-tinted recollections of the past coupled with the present

conundrum of “already been done” has

suspended Western culture in a temporal loop.

“Two Steps Back,” in fact. The

time-locked cultural blockage of an age after Postmodernism has rendered the

“new” profoundly spectral: we are watching, listening and responding to

ghosts. These ghosts are the spectres of

Modernism and pre-Modernism, the last cultural epochs where technological and

biological growth were anywhere near in tandem with one another. Indeed, the “new” is necessarily enshrouded

with quotation marks – even visually, the word is spectral. Unknown to me in the 1980s, the literal ghosts

alluded to in local folklore were in fact the unconscious parental responses to

a time which made more harmonious sense, when there were less technological

leaps to bemoan.

Différance

is the individuation between biological memory, political memory, cultural

memory…it is how Proust’s memories distinguish themselves between Dostoyevsky’s,

how Beckett’s memories are internalised whereas Joyce’s remain

geographical. Escape from Marienbad,

indeed. Différance is the temporal

linguistic rift rent by dromology. Différance is the colloquial vapour trails

left hanging in the air in the wake of cultural imperialism.

Différance

is the family unit with lost unity.

Derrida

likened the spectre of Marx (that phantasmagorical after-image which has

haunted capitalism for over a century) to Hamlet’s father: literally and

etymologically the root spectre at the feast.

Indeed, that crucial textual link was made early on by highlighting that

Hamlet was “the Prince of a rotten state,” allegorically that same rotten state

which was to be found in the wake of communism itself, its ectoplasmic remains congealed

in the scattered debris of the Berlin Wall.

1980s Britain, or its working class communities, had more than it’s

share of this rot: alcoholism, redundancy, solvent abuse, domestic violence,

mass unemployability…all of these were to be found, as a child, beneath the

superficial halcyon sheen of the nuclear family.

This

impression is what always returns when one hears The Fall. The oblique, rumbling production on Dragnet, the keyboard trail on Frightened, the choppy vaudeville of City Hobgoblins. And those words…like tapping into

long-forgotten truths which revealed themselves in layers the more one could

discern them. Listening to any Fall

record was worth a dozen trips to the library and provided a far more

comprehensive (albeit labyrinthine) education than one could hope to gain in

those Thatcherite penal colonies we were forced to attend during the week:

instant psychic Cinerama of a world made up of grotesque (ha!) dog-breeders,

phantom stalkers, Disneyland beheadings and strange conjugations of literary

figures. Mark E. Smith saw himself as a

writer above all else, and it is indeed within those wordscapes that one is

ensnared once those primitive, repetitive rhythms and snarling Northern barks

have either enchanted or repelled you. One

reads The Fall as one reads Deleuze – in layers and multiplicity; the libido in

despair, castrated by its own production.

Listen to Room to Live, or Tempo House and you have a Deleuzian

machine absorbing as it creates. One can

almost hear the ideas forming in Smith’s mind just before he contorts them, the

rhythm section in endless repetition as time strangles the pleasure principle.

Once

one hears The Fall (either as a joyous or attritional experience) one is at

once haunted by The Fall: like Marxism, the time between first contact and

present time is rotten with phantoms.

The “ghosting” effect on an old television broadcast is merely the ghost

of multiplicity, information forced down a tube which is continuously caught up

with itself in a cathode Möbius. The

“captured” cultural elements of the past, ensnared by Smith, become distorted

in much the same way as Francis Bacon would pervert his subjects and, like

Bacon, Smith froze his subjects at their most primal as though intuition led

him to their animal state: Terry Waite, Alan Minter, MR James, Lou Reed and

Doug Yule (in an instant fused into the one chimeric state) – all in a state of

“…becoming Fall.” The industrial

landscapes sonically conjured by a superficially grotesque rumble are another

“becoming,” for in that instantly primal cacophony lay not only the bleak

Conservative wasteland of late-70s and early 80s, but also admitted to the

industry of Blake’s Jerusalem – a

bleakness far sootier and rooted in diaspora than anything suggested by

Kraftwerk or Joy Division. Here was (and

is, captured in essentia) an industry transcending political trend: if Marxism

is the spectre haunting Europe (macro), then The Fall conjure the specificity

of a Britain enslaved to a Marxist ontology, or rather the phantom of

differance which manifested itself in a typically Northern blue-collar attitude

which eternally defies translation.

This

was the Britain one would experience if one watched Coronation Street through a

lens in any way similar to Smith’s – the Barlows’ crepuscular killing sprees,

Kevin Webster copulating with Jack Duckworth’s pigeons in the outhouse to

produce a malformed beak/moustache hybrid, all in those lurid cathode reds and

blues of early colour television, yet with shadows darker than a Castiglione

monoprint. And we respond to those

grotesqueries knowing full well that we – the working class with our fathers

risking life and limb daily at the colliery – are the grotesque products of a

perverted society. Smith took the

narrative experimentation of The Velvet Underground and twisted it to his own

vision, throwing in all manner of literary, cultural and political allusion

along with it - the mystical autodidact Roman Totale XVIII his early

prosopopoeial alter-ego emerging from the song lyrics to commandeer the sleeve

notes. So within, so without.

Music

has been something which comes and goes in my life, with precious few

exceptions. When I wanted to put

together a band at the age of twelve, I was too young to do so to any extent

other than drafting in school friends to help create an undisciplined cacophony

in the spare room. It was, for them,

something to stave off boredom and nothing more. For me, it quickly became the case that I

could entertain myself more effectively by making a cheap guitar and amplifier

sound like something other than a cheap guitar and amplifier: hiding the amp

under a pillow with the bass turned all the way up sounded like the atonal hum

of a building site, whilst striking the strings with metallic objects made for

the sounds of cinematic stabbing (reflecting the potentially lethal act of

striking electric guitar strings with metallic objects in the first

place). I made no further attempt to

form a band until in my early twenties, when any chance of finding like-minded

individuals had been scuppered by the lumpen musical ideals left in the wake of

a withered Brit Pop: young musicians wanted to sound like solo Paul Wellers and

already-existing bands stank of being fully endorsed by their parents, who were

probably in bands which emulated Paul Weller in 1983. There was nowhere to be found the kind of person

who wanted to create the kind of sonic experimentation I needed to make. The Velvet Underground’s currency – which has

always been in fluctuation in the eyes of the mainstream – was at an ebb. Such is the way with being out-of-synch with

things: always one paradigm shift from having a real chance at something

special. In hindsight, of course, I

count my blessings for the music business is among the vilest of industries,

and I then lacked the sheer bloody-mindedness to persist at all costs like Mark

E. Smith always has. More than this, I

lacked the discipline to maintain a single sound throughout anything

approaching a career, much less stick to so singular a discipline as music. This is why the likes of Smith, Billy

Childish and other counter-culture luminaries who doggedly refuse to attenuate

themselves to anything as crass as a marketable sound have to formulate their

own economies – and not just financial economies.

Shane

Meadows’ 1999 drama A Room for Romeo

Brass was filmed in the same village alluded to in the first

paragraph. Shot nine years after I left

the village, there is a marked difference in the landscape of my childhood and

that recreated on the screen, a difference which went beyond

representation. Seeing the village in

Meadows’ film, I felt no nostalgia, no sudden desire to return there. Indeed, aside from the novelty of recognition,

there was nothing to link the me in

the present to the me who recalled

playing in the exact locations now being used as a stage for Paddy

Considine. Partially, this can be

attributed to simple displacement and the passage of time, but more crucially

the topography had altered to such an extent over those nine short years that

my very conception of the village had become the recollection of a ghost, or at

the very least an erasure. My childhood

existed only in my memory, and no amount of old photographs (of which there are

very few) could ever amount to anything more than a multiplicity of

reflection. Time is no longer a thing

which can be measured by temporality alone – of all the images and zeitgeists

left to us by the Twentieth Century, a sense of echoing pastiche is likely the

dominant sensation which has only increased with massive exponentiality to the

present day. Which decade is this year

in the 1990s emulating? To what extent

do the purveyors of culture in 2012 understand the forms and aesthetics they

are aping from 1969?

I

have, since an age too far back in my memory to place with any exactitude, been

in a state of mourning. This is no silly

Freudian claim of being desirous of a return to the womb: personally, I

frequently refer to that oft-repeated Smiths lyric whenever I encounter Freud –

“it says nothing to me about my life.” The mourning I claim is the mourning for a

childhood half received, or indeed a deferral of childhood which was felt just

as (if not more than) keenly during my infancy.

Betraying the above claim, I must nonetheless turn to Freud for his

unheimlich to describe that jarring notion as a child that there was always

something wrong, something awry or missing.

Unheimlich is perversely the

most fitting term for my domestic childhood situation, for the home was

sporadically and decidedly unhomely.

Growing up with alcoholism from an extremely early age means that there

has been no chance for the child to know anything other than a home run through

with alcoholism, and that home being in a relatively (by today’s standards)

tight-knit community means that any social comparisons must be drawn from other

homes which are in some way complicit with alcoholism (few could have not known

that our house was the one with the parent who lapsed wildly into stupors

lasting days and, sometimes, weeks. Yet

very little was ever done to circumvent the vicious circle of dependency: in

fact, the reverse was so often the case).

In such circumstances, one lives in a microcosm of Other: there is

nothing wrong with this picture…and everyone who knows precisely what is not

wrong with the picture knows how to mind their own business about what is not

wrong – at least until their front door is closed.

When

an infant encounters an adult who is drunk, the first instinct is to think of

the adult as “unwell,” which is conveniently confirmed by other adults and

becomes the official euphemism. “Unwell” also means “absent” in such cases,

even if the unwell person is in the same room, because the sober parent has

been purged of all parental virtues, such as responsibility, kindness,

indulgence or accommodation. The entire

architecture of home life is dismantled to such an extent that the very state

of childhood is placed in suspension. If

a parent is too drunk to collect their child from nursery, then that child

ceases being a child in the eyes of nursery staff and becomes a problem. If a child is not in school because of

parental alcoholism, then that child is now a “case.”

But

what is perhaps the most destructive of all are those periods when the parent

is sober: life is less complicated, certainly, and the parent/child bond is

soldered together once more, but there is always the dread – which can occur at

any time, with or without warning or cause – that the unwell will return,

rendering the moments of sobriety something to fear just as much as the periods

of chaos. This, then, is the mourning I

have felt since infancy. Petite morts in

the most literal sense: mourning the death of the home, the death of a childhood

being allowed to live itself out, the small, staggered death of a parent.

I

was six years old in 1984, the year forever burned into scholarly discourse as

the official death of the blue-collar worker in Great Britain. My father worked in the mines, though ours

was a colliery which outlasted many others in Nottinghamshire. Although Calverton Colliery almost survived

the century due to private finance (the office block was the last structure to

be demolished in March, 2000), redundancy hit our household in 1987-1988. The Calverton in A Room for Romeo Brass is the neoliberal perversion of industry:

Vicky McClure’s character works in a fashion outlet in St. Wilfred’s Square,

which was formerly a chemist; Considine’s Morrell is unemployed, friendless and

entirely disconnected from both morality and self, a parody of identity tripping

over itself to fill in the cracks left over from a patchy education and a

(tacitly) fractured home life. This is a

society very much in the process of restructuring itself, redefining its

identity by drawing from its immediate past, its discordant present and its

bleak future. Almost twenty years on and

that future is not so much bleak as eerie: children no longer play in the

streets (an ostensibly glib statement at first glance, but no less true for

it). For children in 2018, socialising

has become compartmentalised into school, after-school clubs and birthday

parties. The common ground of having

parents who worked within a location-specific industry is gone, and in its

place are streets full of adults who are too busy keeping their heads above

water with insufficient McWages to integrate with others on the street – often

because those others command higher wages for less effort, but perhaps more

often because there is little understanding of what the other’s job actually entails.

What once unified communities has alienated it. Mark Fisher adroitly pointed to this

diasporic labour culture as both cause and symptom of depression in his

excellent essay Good for Nothing. The working-class curse of being made to feel

inadequate for professional jobs, whilst feeling inferior (or at the very

least, fraudulent) in office or factory work:

“…because I was

overeducated and useless, taking the job of someone who needed and deserved it

more than I did. Even when I was on a psychiatric ward, I felt I was not really

depressed—I was only simulating the condition in order to avoid work, or in the

infernally paradoxical logic of depression, I was simulating it in order to

conceal the fact that I was not capable of working, and that there was no place

at all for me in society.”

It

is only natural that this phenomenon trickles down to our children. As displaced as we are in our present

economy, this can be nothing compared to a child who feels no tangible

connection to a world both virtual and indifferent. We recognise ourselves (or partial vestiges

of ourselves) in our immediate culture and react to this accordingly, yet when

our immediate culture is purely virtual (such as is the case when a child’s

daily routine consists of school-dinner-bathtime-device, as opposed to a routine from the late Twentieth Century

which was more akin to school-play-play-dinner-play-bathtime-bed), psychic

well-being suffers just as surely as physical well-being suffers from vitamin

deficiency. Children identify with –

and, terrifyingly, become - nebulous,

uncanny forms in video games: forms which have nondescript facial

characteristics, limited movement and lifespans with no value. They are both Geppetto and Pinocchio with no

reference to a higher meaning. Small

wonder, then, that they struggle to place any real value to the social

realm. The mirror stage ceases to

function when the mirror ceases to reflect.

We are now (and have been for some time) in an age of mass childhood

dysfunction which has increased at such exponential speed that psychologists,

behaviourists, therapists (et al) can no longer sufficiently account for

it. This is because the accounting must

come from fields outside of Freudian specificity: the social sciences (as

evidenced by Fisher) are where the answers are to be found, and from a

sociological perspective they are to be found relatively easily. We need only refer to Foucault and thereby

note the homogenisation of the state apparatus (the school being modelled on

the prison, for example) to see the link between this and a gaming platform

such as Roblox, which takes this model to the nth degree. Players create and interact in virtual

cell-like buildings, which can vary between prisons, schools, houses, pizzerias

or indeed any simulacrum of our reality.

Very little distinguishes these artifices aside from superficial décor,

and the tasks each player performs is largely standardised and based on

production / consumption. The neoliberal

ideal supplied (as only the neoliberal ideology would be allowed to) as

plaything for a standardised socialising.

If any suggestion had been made to me (and, I imagine, any other child)

in the 1980s that performing perfunctory tasks in order to achieve virtual

(i.e. non-existent) rewards could in any way be passed off as entertainment or –

even more scandalously – playtime, this would have been dismissed as some

species of Stalinism: a tin-pot attempt at coercing child labour masquerading

as fun. Platforms such as Roblox offer

no conduits for the superego to develop, and creativity is limited to the basic

additions the child can make to their domains.

This is the very business school one imagines when listening to The Birmingham School of Business School

from the 1992 album Code:Selfish:

Weave a web so

magnificent

Disguise in the art of

conceit

….

Deposits prisoner

robotics

Home to their wives

Stepford

Case-carrying

Business School

At

the expense of all else the neoliberal worldview must emulate itself, asserting

its financial and political dominance in self-replication, deceit and a means

to an end mentality (the end of which must ever be kept out of sight and

grasp).

I

was twenty-five when my mother died, just one week after her sixtieth

birthday. Those small, staggered periods

of mourning I had undergone all throughout my life until that point returned,

massively intensified and furiously indignant at the torment I had lived

through. To have my mother’s death

played out in front of me so many countless times, whereby the person who

should have been a constant in my life mockingly replaced by something so

animalistic finally and so swiftly taken from me at a point in my own life when

I should have been adjusting and reacting to the vicissitudes of my own

adulthood felt like the most vicious betrayal of all. Depression had been a factor in my life since

the age of twelve (if I have to give an age to the time when it was finally

recognised that the sense of “wrongness” at home had finally been absorbed by

my own psyche to become an unwellness in its own right), and by the time of my

mother’s death I had already made no less than six attempts at my own

life. Any attempts at academia up to

that point were offset or sabotaged by personal feelings of insufficiency and I

had tellingly fallen into catering - a vocation frequently associated with

verbal abuse and physical suffering. All

relationships I had were a priori doomed to failure, though that only served to

exacerbate the pain when this inevitably became the case. Again, the protracted mourning period playing

itself out.

A

Memorex, then, for the Krakens. These

memories remain buried, submerged beneath countless quotidian events waiting to

be re-activated by sensory stimuli. The

stimuli, though, must be of the time of

the memory in order to function. The

Memorex must be a pure recording.

Ti

West’s 2007 film The House of the Devil

goes further than pastiche: it wants you to believe that it was made in the

early 1980s, down to the camera tints, synth-heavy soundtrack, dialogue and

content (devil worshippers here deliberately chosen to harken back to the

Satanic Panic in the wake of the Richard Ramirez killings). Most tellingly, however, is the film’s title

shot. Filling half the screen in garish

yellow, the title reeks of cheap exploitation horror though the inclusion of

the film’s date in Roman numerals gives pause: the tradition of placing the

film’s title with it’s production date directly underneath with All Rights Reserved is something which

died out in the late 1970s, thus creating not only a jarring anachronism but

also – perhaps most poignantly – turning the charade in on itself. What we are left with is not a reference to

the past, but rather an atemporal, half-remembered throwback which forfeits

historical exactitude in favour of nostalgia for a time which never happened as

it exists in collective memory. The House of the Devil is by no means

alone in this stylised misappropriation: It

Follows, Beyond the Black Rainbow,

The Neon Demon, Nightcrawler, Under the Skin

and Amer are but a small selection

from the hundreds of motion pictures made with an eye to providing the viewer

with that most ultra-postmodern thrill of experiencing the past as they have

always remembered it: not factually, but mnemonically via associations and

cultural connection. The danger of this,

of course, is in the potential for collective memory to wipe out the historical

fact. A Twenty-One-year-old watching

these films today has no first-hand experience of 1984, therefore leaving them

with nothing to distinguish between the two oppositions. Reason concludes that the result of this

phenomena will be an entirely muddled collective memory in 40-50 years whereby

the Twentieth Century will eventually be remembered amorphously and

atemporally.

Though

the above may be a peculiarly altermodernist symptom, its eventual effect is,

to all intents and purposes, what one is listening to on And This Day, Hex Enduction

Hour’s cataclysmic denouement. Time

crashes in on the listener all at once, the preceding fifty-three minutes of

the album serving as individual elements while And This Day serves them all up at once.

In

2018, we are still in the process of mourning (a deferred mourning, but a

mourning nonetheless). We mourn the failed promises of modernism while we

adjust constantly to the increasing pressures of a neoliberal world. For the working classes, we mourn ourselves

as we struggle to ward off the demands of abstract capital. Our ongoing mental and psychic collapse is as

much the product of Victorian Dad ideology as it is lagging concentration in an

age of advanced dromology. “Pull your socks

up” is scandalously still being uttered by mental health workers who themselves

cannot ever hope to reach the bottom of the piles of cases stacking up every

day. Those children lucky enough to be

dealt with in timely fashion are furnished with ADHD statements as readily as

birth certificates, while other children less fortunate (mine included) wait

years to be granted a cursory inspection, before an inevitable non-conclusive

conclusion. The fault lies squarely with the parents, so the official party

line of responsibilisation goes.

Parents, however, are sinking under ever-increasing debt just to stay

above water. For the working classes,

the very concept of a meritocracy is not as ludicrous as it is offensive. Perhaps

this penchant (yearning, even) for the relics of the past – albeit reformatted

to fit in with our collective memory – is nothing less than a coping strategy:

there was a time when those in need would be accommodated, when the poor were

dealt with sympathetically rather than with scorn. And as much as we know this to be far from

the truth, it is a falsehood far more comfortable than today’s crushing

truths. Mark E. Smith was the

ever-present rage against the horrors of neoliberalism: fiercely opposed to the

fol-de-rol of social media and distrusting to the end of a system which

streamlines cultural endeavour to fit the device, Smith took The Fall and made

it rougher as the rest of the world became sleeker. The grotesque salmagundi of sound sculpted in

the 1980s, consisting as it did of harsh Germanic repetition, quasi-Jamaican

barked ad-libbing, Velvet Underground drone and a brash form of working class

country music (country and northern, if you will [and he did]) had, over the last decade, become a feral beast of

unrelenting curmudgeonly fury, primed and aimed at any and all facet of a West

so utterly surrendered to the growing weight of capital.

As

amusing as it may be to recall Smith’s innumerable bon mots, jibes and drunken

slurs collected over the decades, it is nonetheless to miss the point - Samuel

Beckett was no less the caustic wit when in his frequent cups and Jackson

Pollock could just as easily clear a dinner party as Smith could a pub. Yes, I frequently return to YouTube for my

regular fix of Smith’s brusque humour in interviews yet, for the proper stuff,

I delve feet-first into Grotesque and

Hex Enduction Hour. These albums weren’t joking. They meant every rancorous syllable. While Morrissey was regaling us with upturned

bicycles and Oscar Wilde throwbacks, Smith gave us the world red in tooth and

claw, only redder and toothier. And

while the former produced countless soundalikes throughout the eighties,

nineties and to this day, nobody has ever managed to sound like The Fall. Quite right, too.

Comments

Post a Comment