The Nomad Worm or The Nomadological Turn in Contemporary Art

This is a treatise on nomadology. Yet, often more than this it is a treatise on

the rhizomatic influence Gilles Deleuze has had on contemporary art and – on a

much wider scale – Western culture in general.

It is only reasonable, then, that its structure should be nomadic in

nature, fashioned as such more as a tool to illustrate this often problematic

Deleuzian concept than as a homage to A

Thousand Plateaus[1],

his and Felix Guattari’s magnum opus.

Ours is an age when linearity is a matter of both personal

interpretation and artist’s prerogative: from meta referentiality, disruptions

in a given narrative order, prosopopoeia or a more time-honoured allegory. During the course of this dissertation I

shall be using many of these devices, yet the most notable will be prosopopoeia

in the form of Harry Irene, a fictitious art critic who will on occasion

resemble Clement Greenberg, will sometimes reflect the mannerisms of John

Berger or even unashamedly ape Brian Sewell.

Never affected with malice, this gestalt interpretation merely serves to

reflect on the typically modernist attitude which was the hallmark of

mid-Twentieth Century criticism. We can imagine pince nez, and furnish Irene

with them accordingly. Yet, If Irene is

a virtual gestalt of Twentieth Century art criticism, then this of little

significance. Art critics have always

necessarily been spectres at the feast of invention: they help to mould style

by trimming away excess, adding (sometimes) rich commentary and narrative to

artworks and exponentially increasing the culturally affective clout of

same. Conversely, their function can

also serve to stifle and stunt cultural growth.

Perhaps one can say that the text can also be read as an affectionate

lampooning of that profession, although one must therefore remember at all

times that this would merely be subtext.

A lighthearted subtext, certainly, but subtext all the same.

As an artist I have constantly been

nomadic in my practice: this goes hand-in-hand with a mind which is constantly

flitting from one concept to the next, considering the commonalities which

unite otherwise disparate issues and allowing one sole constant throughout my

body of work – myself. From themes such

as father/son relationships, mental health, hauntology, Althusser’s interpellation,

cinema, memory, identity and even the work of Deleuze himself, I have never

remained lingering on any one topic for long, nor has the materiality of the

work remained static. When a viewer once

commented that my work consisted of “everything but the kitchen sink,” I

briefly entertained the idea of sourcing that very item and, early on in my

career when lamenting my own lack of style or idiosyncratic visual coding, a

tutor responded with “you know what?

It’s overrated.”

This dissertation does not seek out the

specific times and places of any nomadological departures per se, and certainly

the aim is not to traipse once more through Twentieth Century art history in an

attempt to temporally tick the boxes which support my thesis. What it will do, however, is suggest artists

whose spirit has either prompted or perpetuated nomadic art practices. Again, this is by no means a left-to-right

recounting of the past as it meets the present for to do so would run counter

to the very phenomena discussed. It will

remain atemporal throughout, much like the indexical numbered lines of flight

detailing specific instances of events which, in one way or another, are

nomadic. It is important that this work

be allowed to stop and start at its own pace, according to its own nature, that

it reads like a Deleuzian plateau.

Oyvind Fahlström, Eddie (Silvie's

Brother)in the Desert, 1966, silkscreen on paper, 17 1/4 x 22 in.

- .

Harry Irene[2], much like other similarly

flamboyant modernists of the day, espoused formalism and unity as the hallmarks

of “good art.” With six years’ boarding

school behind him and an impeccable grasp of Latin, for a while Irene was

considered the Philosopher King of art criticism. The spokes on his bicycle would resonate

machine-like as the art critic weaved his way throughout the London streets

from one gallery to the next.

Good-natured and sympathetic to all, with the notable exception of

artists. By and large, he openly

despised them. His beloved Willem de

Kooning set the benchmark, if one were to ask him, of painterly

excellence. Robert Rauschenberg, on the

other hand, he considered the scourge of the art world – if one were to ask

him, Irene would lay the blame of aesthetic decline almost squarely on

Rauschenberg’s shoulders, and was particularly scolding towards any artist who

appeared to ally themselves with the American.

In 1967 Irene wrote on Conceptual Art “the ill-deserved revival of the

redundant French buffoon.” Typically

dismissive of anything which eschewed the aforementioned two values of

formalism and unity, Irene said this in 1962 of Öyvind Fahlström’s solo

exhibition at Paris’ Galerie Daniel Cordier:

“The

novelty of in-patient logic combined with a flagrant disregard for context

notwithstanding, the Cordier has delivered a flat, jejune show. The painterly has been reduced to the wax

crayon, and Rauschenberg apparently loves it.

The exhibition brochure features the blushing artist rejoicing that

there are like-minded souls in the world.

All structure, such as it is, is purely virtual – blending the political

with the fantastical and presenting the result in works that are only ever two

steps at best above an adolescent’s boredom-breaker may appeal to the radical,

but should not be encouraged if art hopes to maintain its plateau. Cartoon politics and beatnik affectations belong

to the pulps, not the Cordiers.”[3]

The plateau alluded to would be – in 1962

– one more singular and hierarchical than a plateau suggested by Deleuze and

Guattari. Theirs was one of a reciprocal

multitude, while Irene’s was still very much in the nature of the sermon on the

mount.

In 1980, The Fall paid tribute to Harry

Irene in the lyrics to How I Wrote

Elastic Man:

Life

should be full of strangeness

Like

a rich painting[4]

The above couplet, whether Mark E. Smith

at the time realised it or not, also succinctly outlines what Gilles Deleuze

and Felix Guattari referred to as “lines of flight,” and implies by its

imperative that life is only worth living if it encounters strangeness. Analogous to the becoming outlined in the two

volumes which comprise Capitalism and

Schizophrenia, Deleuze and Guattari propose that it is through the

encounter that consciousness and subjectivity are defined. The various and infinite forces which our

universe (that non-transcendental state which the authors refer to as the plane

of immanence) is governed by are always in flux, connecting and passing through

other forces at random and in so doing creating new perceptions and systems of

thought. “Strangeness,” then in this

context should be read as an encounter (be they subjective or objective)

between two disparate forces. Simply

put, the subjective force of an art work upon the viewer only opens up

possibilities for discourse if that art work is unfamiliar, strange or in many

cases ugly, to that viewer. This makes

possible and likely new ways of perception, new modes of thought and new

creative possibilities (for the strangeness perceived by the viewer should, if

interpreted correctly, inspire fresh creative forces which pass through the

viewer-becoming-artist). These

phenomena are not restricted to any cultural discipline (or, as Deleuze and

Guattari would have it, “captured”), but are instead multi-disciplinary in

nature. In this respect, lines of flight

can be traced between contemporary art, cinema, literature or – as the above

lyrical example attests – music. Art is never purely a process of subjectivity:

rather it is emancipatory in the sense that it opens up potentiality. Abstraction becomes a plane of immanence on

which the virtual is perceived as utopian potentialities.

Among Deleuze & Guattaris’ more

crucial themes – in terms of contemporary art-world parlance – is that of

nomadology, which has gradually over recent years become a dominant

practice. The nomadic artist will jump

from materials, themes, ideas and strategies in an ostensibly random manner,

whilst retaining a core constant (on the plane of consistency, staying with

Deleuze) which is more often than not the artist him or herself. This text should therefore focus on nomadic

practices, their origins and their implications, the central idea that art

should retain a chaotic sensibility in order to remain relevant in a chaotic

word. More than this, though, is the

sense that while a given artist superficially seeks to create order from chaos,

there is also a strong element of the opposite: to create a chaotic linguistic

framework from a pre-existing order, and then to reassemble the elements taken

apart into a seemingly chaotic bricolage, which is in itself deceptively

ordered.

To place this phenomenon into an

historical context, it is perhaps useful to go back to Post-Conceptual Art,

that 1970s movement which not only reintroduced materiality to conceptual

practice, it added new and emergent materials in order to expand the

potentiality of same. John Baldessari is

often credited with creating both Post-Conceptual practice and its taxonomic

during his tenure at the California Institute of the Arts, although one could

also argue that the basis for Post-Conceptualism was already put in place by

the Fluxus movement. Certainly,

Happenings bore all the extra-material hallmarks of Post-Conceptual art, though

artists who were the product of Fluxus were already exhibiting nomadic traits

as far back as the 1960s. Yet

Baldessari, in 1973, was using strategies of games in his work Throwing Four Balls in the Air to Get a

Square (best of 36)[5]

which mirrored those of Swedish multimedia artist Öyvind Fahlström. Fahlström can be said to be a forerunner of

nomadic practices.

John Baldessari: Throwing Four Balls in the Air to Get a Square (best of 36).

|

|

Line

of Flight #1: “Everyone is an artist,”[6] Joseph Beuys once famously

said. Rather than a trite throwaway

statement, Beuys perfectly sums up the Deleuzian concept. Where nomadology and the rhizome resonate

most profoundly is in the biological, rather than the linguistic (although we

may reason that the two are not mutually exclusive). If everything is in a perpetual state of

becoming (desire, as Deleuze would have it), then everything is subject to

affect: one body affects another to varying degrees of intensity. What Beuys proposes is that the substance of

art (whatever form this may take) increases the intensity of the affect. A person who spends their entire life without

once putting brush to canvas, without moulding clay or taking any photographs

is still an artist in the affective sense, in that their very existence will

resonate with another living thing. Art,

as Wittgenstein once said, is a semiotic triangle – a thing is art if it

“arts,” thus affecting the receiver.

Human beings, by their very linguistic nature, are artists due to

communication.

Irene had already dismissed Fluxus the

previous decade as “Flatus.” Having met

Joseph Beuys in Germany, he had advised the artist to purchase for himself a

proper pair of trousers.

Irene would later – in 1978 – reverse his

opinion of Fahlström somewhat, citing the “latent and intersticial nature” of

his work. In accordance with the

paradigm shift brought about by Baldessari’s post-conceptual departure, Irene

was but one of a number of critics who began to realise the potential of the

idea as opposed to the finished work. If

Fluxus began to erode the material norms of art practice, then post-conceptualism

re-assembled art practice in a way which, for commentators such as Harry Irene,

was perhaps too much of a shock to traditional values to at first work in the

same manner as previous decades.

Rather than pertaining to actual nomadic

people, nomadology is simply an illustrative tool to suggest that we may think

and write without reference to hierarchical, arborescent models. Favouring the rhizomatic at all times,

Deleuze and Guattari propose a means of production which is emancipated from

any pre-established linguistic framework.

The painter should paint without reference to other painters, the

playwright (like Beckett) should write according to their own haecceity and to

the flames with Shakespearian orthodoxy.

Line

of Flight #2: in 1966, Tom Phillips purchases a

second-hand copy of W.H. Mallock’s obscure Victorian novel A Human Document[7]

whilst in a furniture repository with painter R.B. Kitaj. He sets himself the task of reworking every

page in the book, by inking over, deleting and otherwise mutating the story

into an entirely new and rhizomatic narrative interpretation. Completed in 1973 and exhibited that same

year, Phillips’ A Human Document Redux,

now retitled A Humament[8],

was published in its new incarnation in 1980.

Since then the novel has mutated even further, with Phillips re-working

his interpretation and developing this into an opera. According to Phillips, “Once I got my prize

home I found that page after randomly opened page revealed that I had stumbled

upon a treasure. Darting eagerly here and there I somehow omitted to read the

novel as an ordered story. Though in some sense I almost know the whole of it

by heart, I have to this day never read it properly from beginning to end.”[9] This is precisely how Deleuze and Guattari

propose that the reader approach A Thousand

Plateaus, ignoring the left-to-right linearity of a book in any traditional

sense.

Nomadology is subject to lines of flight,

and the biunivocal relations between bodies which occasion these lines of

flight. The nomadic artist flags vectors

and creates other lines of flight towards new vectors. Consider the work of Ken + Julia Yonetani,

which “explores the interaction between

humans, nature, science and the spiritual realm in the contemporary age,

unearthing and visualizing hidden connections between people and their

environment.”[10]

This self-assessment, courtesy of

the duo’s website, already sounds nomadic yet, when we consider any

collaborative venture we may conceive of two (already nomadic) vectors meeting

to create a further (two-fold) nomadic vector.

This vector, then, contains an exponentially greater potentiality. This phenomenon bases itself on the concept

of the smooth and striated space.

Striated space being hierarchical and of the state (that which can be

counted and occupied in sedentary steps), whilst the smooth is rhizomatic,

multitudinous and decidedly more democratic.

|

|

Tom Phillips: a graphic score from the

opera Irma, adapted from A Humament.

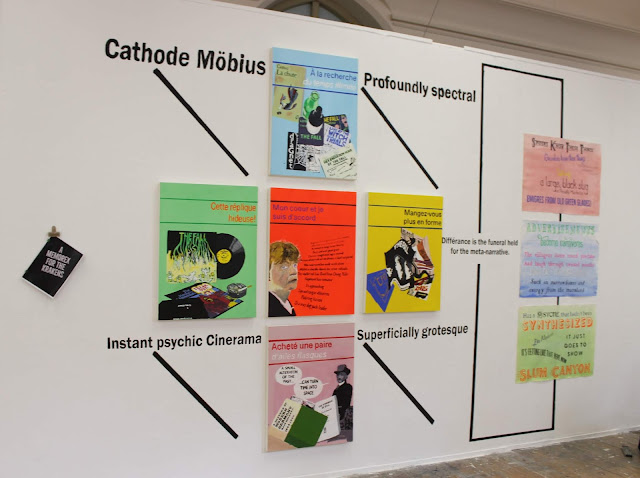

Chapter

Two: In Which Style is Forsaken in Favour of a Globalised Non-System of Signs

Can art be traced on a map with any degree

of exactitude? By this, we may imagine a

vast chart which historically positions movements, artists, themes and media,

imagining further that these can be connected according to commonalities: which

themes link two otherwise seemingly disparate art practices? Certainly, we can draw inferences from social

and political issues, in that prevalent societal factors in the 1950s, for

instance, can still be attributed to the contemporary work – societal factors

are never purely tied to one particular epoch.

Line of Flight #3: 2013. Raqs Media Collective bring their multimedia

project The Last International to New York’s Performa 13 biennial. From the germ of Karl Marx and Friedrich

Engels' idea to move the Council General of the First International Working Men's Association to New York City in

1872, the exhibition develops into “a deep sea dive, head-first, into the

future, and into infinity” which “stages debates, a wine-drinking symposium on

time, involves a runaway rhinoceros, a time travelling bicycle, a conversation

between a yaksha and a yakshi, as it turns mathematics and botany into poetry

and creates a ruckus out of concepts, questions, symbols and totems.”[11] Raqs transcend linear time and geographical

space, imagining temporalities and realms which might be considered

hauntological. Jacques Derrida

postulated that Marxism would haunt Western society from beyond the grave in an

omnipresent, miasmic manner neither alive nor dead.[12] Raqs do not indulge in prosaic nostalgia:

they re-imagine the past as a precursor to a present that never was.

Beyond that which is immediate in art,

past issues of form, colour and content, lies a subtle, reflexive

mechanism. Shadows present themselves in

the varying distances between the machinic apparatuses of the work and the eye;

the eye and the brain. These shadows are

interpreted in tandem with the more tangible, visual stimuli to make up a

process of affect (the ability to affect and be affected) which may or may not

immediately be perceived by the subject.

Often, the encounter is the essence of art, a trend which has persisted

throughout the latter half of the Twentieth-Century and has found its own

milieu in Relational Aesthetics (for what else could we term this affective

discourse if not “relational”?). Relational

Aesthetics is now a central fixture of an art market which has long celebrated

the rhizomatic, the nomadic and the affective yet can more throroughly be

traced back to Fluxus.

We

take the view that Deleuze and Guattari’s prodigious invention of concepts

should be understood as an attempt to create a new set of coordinates for

thinking that can and should be modified to suit new circumstances and new

questions. [13] (Buchanen & Collins,

2014, P. 2)

Art history has proven time and again that

political and social entropy leads to multiple points of departure in art

practice orthodoxy: Dada owes its

inception to the First World War, the decidedly nomadic catalogue of Ilya

Kabakov is a by-product of Social Realism.

It is perhaps churlish to expect an artist’s milieu to remain the same

in a world in a constant state of flux.

In an age of rebranding, rebooting, re-shuffling and profound

uncertainty, art which rigidly adheres to an aesthetic model is now more often

than not seen as a trifle old hat.

We can observe here that nomadology had

already been a practice and attitude within the art world long before Deleuze

and Guattari had coined the term, and had indicated a shift towards the virtual

and latent which has since become standard vernacular. Artists, like writers, are involuntary

narcissists. Both fabricate worlds in which said artist’s ego has the dominant

ideology, and both dictate life and death according to their whims. Every

writer and every artist is God to their individual micro-disciplinary practice,

a practice which we can perceive as a world, or sphere. If we were to create a

model of the seemingly endless practices being engaged at any one time, we

would see an actual world filled with these spheres orbiting one another,

feeding off of a shared, reciprocal energy. To begin any kind of creative

endeavour is to feed from and absorb the energies flowing from these

multiplicitous bodies, and to negotiate the regulations governing these. The

artist borrows and re-conditions: nothing is purely genius. In this sense art

is always a collaborative process, allowing multiple voices to be heard to

varying degrees of intensity. This process has previously been referred to as a

constellation, though art practice in the 21st Century has become a thing decidedly

more immanent, allowing literal connections, juxtapositions and collaborations

to occur. The artist, we can argue, who does not engage culturally, socially or

creatively with the spheres in orbit around them must either be an artist of

the most profound genius, or no artist at all. We may also think of the artist

as the zeitgeist of their particular field, in that an artist cannot help but

be a vector in a specific chain of semiotic connections starting with

obsessions and inspirations, contemporary osmosis and going on to include those

works which the artist has necessarily inspired. Naturally, the number of

“inspirational” vectors both before and after the artist’s own vector can be

nigh-on infinite, and each prone to mutation – for the flow of creative energy

goes backwards as well as forwards. We retrospectively attribute aspects culled

from other sources to a piece of work after we have encountered the second

pieces of work, altering and mutating the meanings and semiotic representations

to both primary and secondary sources. Indeed, in this respect are there any

longer primary or secondary pieces of work? The present is irreducible to any

singularity. This is what Bergsonism[14] teaches us, and what

common sense forces us not to forget. The present can only ever exist in any

quantifiable measure as a memory, in which case it is imbued with attributes

gleaned from the fanciful whims of subjective recollection (an object observed

by many people five minutes ago is already undergoing an erosion of reality

whereby the individual recollections of these many people have themselves

trailed off into the unstable areas of perception, association and

interpretation).

Öyvind Fahlström connected the semiotic

schemata of Fluxus with the lexicon of popular culture in a way which has now

become familiar within galleries and biennials: understanding the simple maxim

that society and culture are in a perpetual symbiotic loop with one another and

adjusting the linguistic framework of his art accordingly. Five decades later, Franck Scurti is doing

much the same thing, albeit from a decidedly altermodernist perspective. Compare Fahlström’s appropriation of Robert

Crumb’s Meatball cartoon for his 1969 sculptural assemblage Meatball Curtain (for R. Crumb)[15] with Scurti’s hand-drawn

comic insert for his 2002 exhibition at Switzerland’s Kunsthaus Baselland. Both employ the semiotic tactics of Marcel

Broodthaers in their playful linguistic displacement. Consider 1974’s Les Animaux de la Ferme (The Farm Animals)[16]: illustrations of multiple breeds of cow with

their actual taxonomies replaced by car manufacturers. A tactic derived from Magritte, certainly,

yet altogether more playful and with a more cynical eye. This is among Broodthaers’ more renowned

pieces, and serves to throw the observer into a nonsensical black hole.

This practice is today lauded among the

echelons of criticism, unlike in Fahlström’s time, which suffered from a

modernist reactionary backlash. Franck

Scurti enjoys higher praise from contemporary critics such as Nicolas

Bourriaud:

It

is through his writing that Scurti distinguishes himself among the great French

artists of his generation, including Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, Dominque

Gonzalez-Foerster and Xavier Veilhan.

Yet for all that he does not stand out because of a formal trademark, a

formula that can be infinitely repeated.

His “style,” if that term must be employed, lies rather in a movement

toward assemblage, a personal phrasing, not in some visual code bar that is easily

spotted among a thousand others. He

seems to make it a point of honor (sic) never to repeat the same figures, even

to change his working principle with each new show.

[17]

(Bourriaud, 2002, P. 19)

Scurti’s offbeat milieu is to direct idea

into already-present social matter, to transmute the semantic drift of signs

and apply a meaning that is certainly rhizomatic. For 2000’s video installation Colors, Scurti observed a football match

between Ireland and France held in Dublin where various corporate sponsors had

ill-advisedly painted their corporate logos upon the pitch. As the rain started to fall, the paint

diluted and became tacky, covering the players in these corporate,

interpellative primaries. There are

several ways in which we can read this: one interpretation would be of a

capitalist spillage, whereby the economic machine becomes jammed with its

subjects; another reading would be the cross-cultural accident of a sporting

event resembling an art “happening.”[18] The following year, a gallery in Lyon was

temporarily taken over by a clothing manufacturer making cheap t-shirts. Each day a different cartoon was printed on

the shirts reflecting on the day’s practices.

In 2013, Scurti put his own spin on Broodthaers’ series of mussel pots

by filling a snakeskin suitcase with popcorn, while an interview given to

Blouin Art (with the headline “Duchamp

Prize Nominee Franck Scurti on Being an Artist Without a Style”) Scurti

said “I really think that things are happening elsewhere today. Don’t you kind

of feel as if you’ve seen everything? The phrasing is more important than the

style, I believe.”[19]

The artist without a style, while

immediately striking the reader as a pejorative, is perhaps one of the more

fundamental elements of nomadology. To

forsake geographic restrictions, ontological categerisation or indeed to eschew

any sedentary restrictions is to take full responsibility for one’s own

freedom: to discard the State we must truly discard the State, and in this we

cannot expect to retain a State-defined, repeatable identity.

Chapter

Three: Harry Plays Go!

Line of Flight #4: In 1980, Peter Greenaway delivers The Falls, a feature-length absurdist

narrative concerning the mysterious Violent Unknown Event (VUE). Formerly a student at Walthamstow College of

Art, Greenaway then begins a film career which retains many of his art school

traits.[20] Throughout his career, Greenaway references

his cultural background and persistently returns to the prosopopoeial character

Tulse Luper, who lingers on the narrative edge of much of Greenaway’s films.

Line of Flight #5: Prior to his death in

1986, Harry Irene delivers a two-hour lecture which is itself essentially

nomadological. Beginning with Irene

singing the praises of Nam June Paik (much to the bewilderment of those in the

audience who are familiar with Irene’s previous writings) and comparing the

Korean’s work to that of Auguste Rodin.

With a full appreciation of Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus to his credit, Irene postulates that the smooth

sculptures of Rodin have, Via Paik, been re-interpreted as striated and found a

new smoothness in the artist’s appropriations of television sets and radios,

and particularly focuses on Paik’s robotic assemblages:

“The

robot in this instance is nothing less than a self-contained monad. It is a haecceity as much as it is synecdoche

– the thing is the body and the bodies form the thing. Perhaps our emerging media works best in

unity, or perhaps the sum of its parts it entirely irrelevant. This is of no consequence given that our

world is inescapably built of this technological fabric, as intransigent and

unmoveable as Rodin’s marble.”

Irene then goes on to postulate that the

cinematic output of David Lynch proved the futility of Freudian interpretation,

citing the director’s latest Blue Velvet[21]

as an attack on modern psychoanalysis because the entire film is bookended by

the camera going both inside the human ear and passing out of the ear. Irene theorises that the film therefore only

exists inside the subconscious and refuses to extricate itself from the same

until it becomes convenient for the director to do so. Few present in the audience can see the logic

in this, though they are more than satisfied that Irene has become that most

miraculous of things: the State Machine which has become the War Machine. Typically the nomadic, eventually, becomes

the sedentary. The War Machine becomes

the State Machine as it attempts to preserve its own order. The champions of Abstract Expressionism

eventually became its protectors – bulwarks against the oncoming storm of

postmodernism. So, for Harry Irene to

become an exemplar of this phenomenon in reverse is something startlingly

unique. Irene, a lifelong proponent of

chess, and the occasional school champion of same, has recently taken up the

game of Wei Chi. Whereas chess is fixed and rigid, Wei Chi (or

Go, as is its Western nomenclature) is ever-expansive (infinite, even),

observes a few simple rules and allows for a fluid competition. The game is only over when one or both

players decide that enough is enough.

One imagines that if Max von Sydow had challenged Death to Wei Chi

rather than chess, the film would still be playing out today.[22]

“Chess

pieces are coded; they have an internal nature and intrinsic properties from

which their movements, situations, and confrontations derive. They have qualities;

a knight remains a knight, a pawn a pawn, a bishop a bishop. Each is like a

subject of the statement endowed with a relative power, and these relative

powers combine in a subject of enunciation, that is, the chess player or the

game’s form of interiority. Go pieces, in contrast, are pellets, disks, simple

arithmetic units, and have only an anonymous, collective, or third-person

function. “It” makes a move. “It” could be a man, a woman, a louse, an

elephant… But what is proper to Go is war without battle lines, with neither

confrontation nor retreat, without battles even: pure strategy, whereas chess

is a semiology.”[23]

(Deleuze

& Guattari, 1986, P. 4-5)[24]

How can we take this passage and apply it

to art practices? Key words such as

“coded” and “Semiology” can here be read as hallmarks of a closed and distinct

practice (i.e. that of painting), whereas in Go the authors describe a

“springing up at any point,” and “movements not from one point to

another…without aim or destination.” We

can understand this last as being of the rhizome.

Deleuze and machinery are somewhat

synonymous. The War Machine, the State

Machine, etc. The State Machine is

static and sedentary. We can look upon

this is the machine of bureaucracy, that thing which has become fixed and

immobile due to its own inability to expand and mutate – bureaucracy stunts

growth, as it were. The State apparatus

apportions and distributes territory and marks out borders. The War Machine, however, is subject to

change. It plots its own territory according

to its own arbitrations. It affects, is in a constant state of becoming and is

by its very nature nomadic. The mirrored

affect in contemporary art is primarily an intellectual one, in that the

artist, when once would be disciplined and produce according to history and

contemporary tutelage, now pays little mind to the historical regime of

artistic discipline. Codings and

de-codings no longer function in the same way, thanks also to the capitalist

and – perhaps more so – neo-liberal paradigm shifts within our very language.

If we consider the social factors

contributing to the late-Twentieth Century nomadological turn in art, then the

most obvious event would be the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe in

1989. Before this, countries were

silenced – the suppression of artistic freedom was a la mode for a regime which

allied itself with More’s Utopia. East

Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria had literally no presence on the

global art scene whilst the Berlin Wall stood.

Borders, both literal and metaphorical, were dropped overnight. That same year Centre Georges Pompidou hosted Magiciens

de la Terre, billed as the world’s first truly global art exhibition, it

sought to sought to correct the problem of “one hundred percent of exhibitions

ignoring 80 percent of the earth.”[25] It would be churlish to assume that these two

were events were not connected: Communism is a literal State Machine, and its

dissolution here literally gives was to the nomadic.

We shall conclude with a reverential mention

of Michael Haneke’s 1997 TV film Das

Schloß (The Castle),[26]

in which the director explicitly acknowledges Franz Kafka’s original,

unfinished text[27]. The film ends with sheer abruptness, as Kafka

wrote (or, indeed did not write it), with K traipsing through the snow. He never gains entrance to the castle, nor is

the bureaucracy in place to prevent this given any resolution. It is problematic to offer any absolute

conclusion on the topic of nomadology, for it is both an ongoing phenomenon

and, in many ways, has always been there on the horizon of our society and

culture. If the fall of communism led to

a nomadic rupture, then the same can be said for each time capitalism gives way

under pressure. The War Machine exists

on the border of the State, and can be said to be the very thing which applies

pressure to the apparatus. Kafka is

synonymous with the bureaucratic machine, so the novel’s abrupt ending – though

technically an unfinished work – is the most profound way for it to

finish. Haneke reflects on this, and

pays homage to its nomadic nature by allowing his film to just…stop. I, in turn, pay homage to both Kafka and

Haneke by following suit.

[1]

Deleuze, G., Guattari, F. and Massumi, B. (1993). A Thousand Plateaus.

Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

2 Smith, M., Scanlan, C.,

Hanley, S. and Hanley, P. (1980). How I

Wrote Elastic Man. [vinyl] Manchester: Rough Trade.

3 Baldessari, J.

(1974). Throwing Four Balls in the Air to Get a Square (best of 36).

[8 color photographs] Not exhibited.

4 Mallock, W.

(2005). A Human Document. United States: Elibron Classics.

5 Phillips, T. and

Mallock, W. (2005). A Humument. New York, N.Y.: Thames &

Hudson.

6 Tomphillips.co.uk.

(2018). Tom Phillips - Tom Phillips's Introduction to the 6th Edition,

2016. [online] Available at:

http://www.tomphillips.co.uk/humument/introduction [Accessed 16 Nov. 2017].

7 Kenandjuliayonetani.com.

(2018). Ken + Julia Yonetani 米谷健+ジュリア – collaborative artists.

[online] Available at: https://kenandjuliayonetani.com/en/ [Accessed 2 Jan.

2018].

8 Raqsmediacollective.net.

(2018). .:: Raqs Media Collective ::.. [online] Available at:

http://www.raqsmediacollective.net/works.aspx# [Accessed 8 Jan. 2018].

9 Derrida, J.

(2012). Specters of Marx. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

10 Buchanen, I &

Collins, L (eds) (2014), Deleuze and the Schizoanalysis of Visual Art

(Schizoanalytic Applications). London:

Bloomsbury

11 Fahlström, Ö.

(1969). Meatball Curtain (for R. Crumb). [Enamel on metal,

plexiglas and magnets] Barcelona: Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona

(MACBA).

12 Broodthaers, M.

(1974). Les Animaux de la Ferme (The Farm Animals). [Lithograph on

paper (edition of 100)] Various: Various.

13 Bourriaud, N.,

Sans, J. and Durand, R. (2002). Franck Scurti. Paris: Palais de Tokyo.

14 Scurti, F.

(2000). Colors. [Video Installation (3 Screens), Master Betacam]

Angoulême: La collection du FRAC Poitou-Charentes.

15

www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/831686/duchamp-prize-nominee-franck-scurti-on-being-an-artist-without

[Accessed 18 Nov. 2017].

16 The Falls.

(1980). [film] Directed by P. Greenaway. Gwynedd, Wales: British Film Institute

(BFI).

17 Blue Velvet.

(1986). [film] Directed by D. Lynch. North Carolina: De Laurentiis Entertainment

Group.

18 The Seventh

Seal. (1957). [film] Directed by I. Bergman. Filmstaden studios, Sweden: AB

Svensk Filmindustri.

19 Deleuze, G. and

Guattari, F. (1986). Nomadology. New York, NY, USA: Semiotext(e).

20 Steeds, L. and

Lafuente, P. (2013). Making art global. London: Afterall.

21 Das Schloß

(The Castle). (1997). [film] Directed by M. Haneke. Germany; Austria:

Österreichischer Rundfunk (ORF); Wega Film; Arte; Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR).

[1] Deleuze,

G., Guattari, F. and Massumi, B. (1993). A thousand Plateaus.

Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

[2] Whilst

the character of Harry Irene is fictional, it should be mentioned that this

author has named him after a song from Captain Beefheart’s 1978 album Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller),

for no greater reason than whimsey.

[4] Smith,

M., Scanlan, C., Hanley, S. and Hanley, P. (1980). How I Wrote Elastic Man.

[vinyl] Manchester: Rough Trade.

[5] Baldessari,

J. (1974). Throwing Four Balls in the Air to Get a Square (best of 36).

[8 color photographs] Not exhibited.

[6]

The quote, whilst attributed to Beuys, appears to have no source of

origin. It is perhaps useful to think of

this as something mentioned in passing.

[7] Mallock,

W. (2005). A human document. United States: Elibron Classics.

[8] Phillips,

T. and Mallock, W. (2005). A humument. New York, N.Y.: Thames &

Hudson.

[9] Tomphillips.co.uk.

(2018). Tom Phillips - Tom Phillips's Introduction to the 6th Edition,

2016. [online] Available at: http://www.tomphillips.co.uk/humument/introduction

[Accessed 8 Jan. 2018].

[10] Kenandjuliayonetani.com.

(2018). Ken + Julia Yonetani 米谷健+ジュリア – collaborative

artists. [online] Available at: https://kenandjuliayonetani.com/en/

[Accessed 8 Jan. 2018].

[11] Raqsmediacollective.net.

(2018). .:: Raqs Media Collective ::.. [online] Available at:

http://www.raqsmediacollective.net/works.aspx# [Accessed 8 Jan. 2018].

[12] Derrida,

J. (2012). Specters of Marx. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

[13] Buchanen,

I & Collins, L (eds) (2014), Deleuze and the Schizoanalysis of Visual Art

(Schizoanalytic Applications). London:

Bloomsbury

[14]

Henri Bergson (1859-1941), French philosopher whose works Time and Free Will (1889) and Matter

and Memory (1896) were hugely influential for Deleuze.

[15] Fahlström,

Ö. (1969). Meatball Curtain (for R. Crumb). [Enamel on metal,

plexiglas and magnets] Barcelona: Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona

(MACBA).

[16] Broodthaers,

M. (1974). Les Animaux de la Ferme (The Farm Animals). [Lithograph

on paper (edition of 100)] Various: Various.

[17] Bourriaud,

N., Sans, J. and Durand, R. (2002). Franck Scurti. Paris: Palais de Tokyo.

[18] Scurti,

F. (2000). Colors. [Video Installation (3 Screens), Master Betacam]

Angoulême: La collection du FRAC Poitou-Charentes.

[19] www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/831686/duchamp-prize-nominee-franck-scurti-on-being-an-artist-without

[Accessed 8 Jan. 2018].

[20] The

Falls. (1980). [film] Directed by P. Greenaway. Gwynedd, Wales: British

Film Institute (BFI).

[21] Blue

Velvet. (1986). [film] Directed by D. Lynch. North Carolina: De Laurentiis

Entertainment Group.

[22] The

Seventh Seal. (1957). [film] Directed by I. Bergman. Filmstaden studios,

Sweden: AB Svensk Filmindustri.

[23] Deleuze,

G. and Guattari, F. (1986). Nomadology. New York, NY, USA:

Semiotext(e).

[24]

It is worth noting that although Nomadology:

The War Machine was its own plateau in A

Thousand Plateaus, the chapter was later published in its own right. Given the importance of the plateau to this

dissertation, I have chosen to cite directly from the latter publication.

[25] Steeds,

L. and Lafuente, P. (2013). Making art global. London: Afterall.

[26] Das

Schloß (The Castle). (1997). [film] Directed by M. Haneke. Germany;

Austria: Österreichischer Rundfunk (ORF); Wega Film; Arte; Bayerischer Rundfunk

(BR).

Comments

Post a Comment